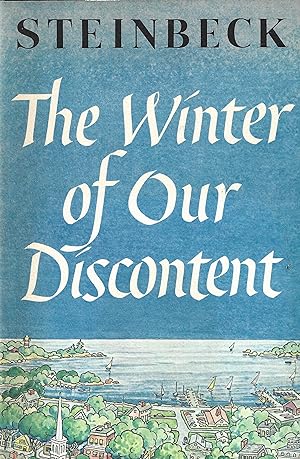

JOHN STEINBECK SIGNS A BEAUTIFUL FIRST EDITION OF HIS FAMOUS WORK, ‘THE WINTER OF OUR DISCONTENT’

The Winter of Our Discontent is John Steinbeck’s last novel, published in 1961.

First edition, presentation copy of Steinbeck’s final novel, one of only 500 examples (with only a few known inscribed examples), which, along with The Grapes of Wrath, are considered his masterpieces. Octavo, original cloth. Association copy, inscribed and signed on the front free endpaper by John Steinbeck to engineer, adventurer and scientist, Willard Bascom and his wife, Rhoda. Steinbeck wrote about Bascom and his work with ‘Project Mohole’, an attempt in the early 1960s to drill through the Earth’s crust, in an article that appeared in the April 14, 1961 issue of Life Magazine. Near fine in a near fine dust jacket. Jacket design by Elmer Hader. Lettering by Jeanyee Wong. Photograph by William Ward Beecher. An exceptional association.

In awarding John Steinbeck the 1962 Nobel Prize in Literature, the Nobel committee stated that, with The Winter of Our Discontent, he had resumed his position as an independent expounder of the truth, with an unbiased instinct for what is genuinely American. Ethan Allen Hawley, the protagonist of Steinbeck’s last novel, works as a clerk in a grocery store that his family once owned. With Ethan no longer a member of Long Island’s aristocratic class, his wife is restless, and his teenage children are hungry for the tantalizing material comforts he cannot provide. Then one day, in a moment of moral crisis, Ethan decides to take a holiday from his own scrupulous standards. Set in Steinbeck’s contemporary 1960 America, the novel explores the tenuous line between private and public honesty, and today ranks alongside his most acclaimed works of penetrating insight into the American condition.

Writer, painter, photographer, cinematographer, miner, archeologist and iconoclastic scientist, Bascom joined Scripps in 1951 and set out to sea with the revolutionary Capricorn Expedition. Exploring the bottom of the equatorial Pacific Ocean, Bascom and others gathered information about the Earth’s crust that formed the basis for the geological theory of plate tectonics.

Diagnosed with bone cancer during the expedition, Bascom was said to take unusual risks, theorizing that he had only a few months to live and one chance to make his mark. But he subsequently subjected himself to unusual doses of radiation and conquered the cancer.

Leaving Scripps in 1954 to become technical director for the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, D.C., Bascom organized and directed Project Mohole, the pioneering attempt to pierce the Earth’s crust. Using an oil-drilling ship off the coast of Mexico near Guadalupe Island at a time when the record depth of water in which drilling had been done was about 400 feet, Bascom drilled under 11,700 feet of water to obtain the first samples from what he called the Earth’s “second layer.”

John Steinbeck went along and wrote about the startling scientific adventure for Life magazine. Bascom himself detailed the Mohole experience, which later was abandoned by Congress because of its cost, in his 1961 book, “A Hole in the Bottom of the Sea: The Story of the Mohole Project.”

The many-faceted Bascom, once a mining engineer, shifted direction in 1962 to form Ocean Science and Engineering Inc., and a decade later Seafinders Inc. He used his deep-sea drilling expertise first to search for diamonds for the De Beers company off the coast of South Africa, and later to locate ancient shipwrecks.

His work took him around the world, including rivers in Vietnam during the war there. And in 1962, according to a secretive civil case he brought in San Diego more than a decade later, he proposed a daring plan to the Air Force and the CIA for raising sunken Soviet missiles. Bascom’s suit claimed he had patented the method. His plan was rejected, but his ideas were applied by the controversial ship Glomar Explorer, which was discovered trying to salvage a Soviet submarine for the CIA in 1974.

Among the historic ships Bascom found were a Spanish galleon called the Nuestra Senora de la Maravillas, off the Bahamas; a wreck off Greece that produced three major bronze statues for the Greek National Museum in Athens; and the paddle-wheel steamer Brother Jonathan, sunk in 1862 off the coast of Northern California.