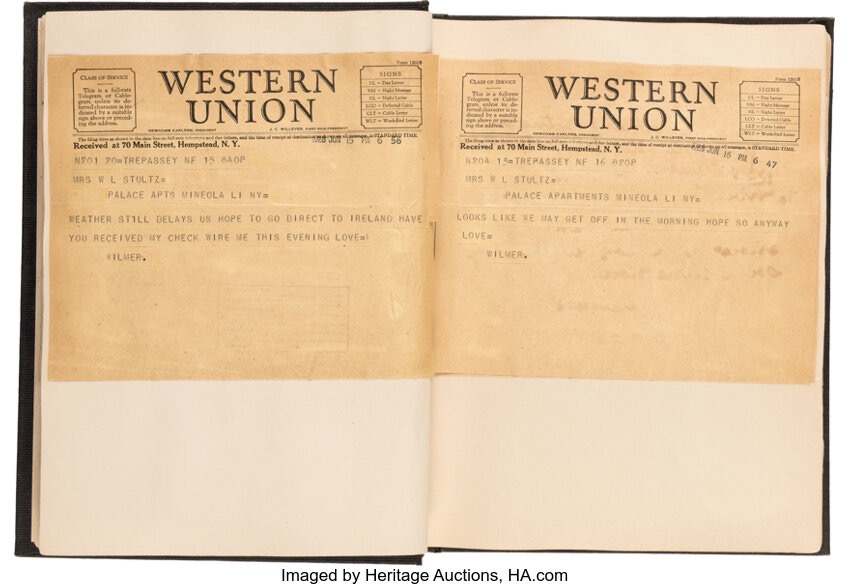

Historic Amelia Earhart Atlantic flight archive of pilot, Wilmer Stultz, including telegrams sent to his wife describing the delays and final success flying across the Atlantic with Amelia Earhart, announcing their arrival in Wales “after 20 hours and 40 minutes“

Wilmer Stultz Archive of Telegrams Documenting Amelia Earhart’s Historic Flight Across the Atlantic. Together with his original pilot license signed by Orville Wright. A series of sixteen telegrams (each 7 7/8 x 6 1/2 inches) dated June 3 to July 3, 1928 through which Stultz apprises his wife, Mildred, of the delays experienced at Trepassey Harbor, their prospective flight date, and eventual historic landing with Earhart on June 18 “after 20 hours and 40 minutes.”

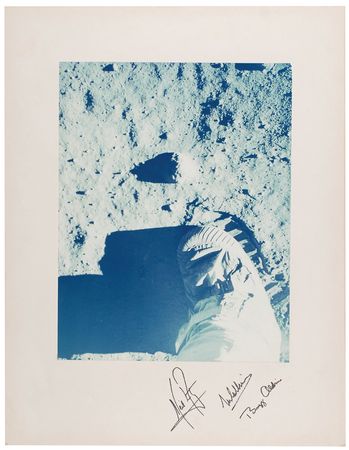

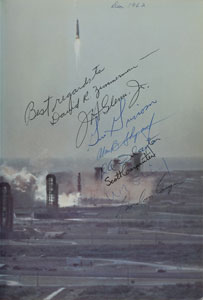

In 1928, Amelia Earhart was chosen to become the first woman to fly across the Atlantic Ocean, an endeavor that would bring her international fame and mark a significant milestone for women in aviation. The selection was made by publisher, George P. Putnam, who sought to capitalize on the growing interest in aviation and gender equality. Earhart’s background as a pilot, combined with her poise and determination, made her an ideal candidate for the flight.

Although the flight was celebrated globally and cemented Earhart’s status as a pioneering figure in aviation, it was also a significant accomplishment for Stultz, as only a handful of pilots had successfully completed the feat.

On June 4, 1928 Stultz sends notice of the crew’s arrival in Trepassey and adds that they “HOPE TO PROCEED TOMORROW.” From June 5 to June 11 he sends six telegrams reporting on pending departures and further delays due to weather conditions. On June 12 he reports an attempted departure: “TRIED TO LEAVE BUT FAILED TO GET OFF WILL TRY AGAIN TOMORROW.”

The following day he reports another failed takeoff: “TRIED AGAIN THIS MORNING BUT FAILED. REDUCING LOAD AND LEAVING FOR AZORES IN THE MORNING.” Three telegrams from June 14-16 report further delays due to weather. Mildred records two holographic radio messages sent by Wilmer on June 17 reporting his progress during the flight and that everything is fine.

On June 18, Wilmer sends notice of their arrival in Burry Port. Wales: “FINALLY LANDED HERE OKAY AFTER TWENTY HOURS AND FORTY MINUTES.” Notably, Amelia Earhart would title her famous book recounting the flight, “20 Hrs. 40 Min”.

The telegrams are mounted individually on the pages of a scrapbook (9 3/8 x 11 3/8 inches) kept by Mildred and contain fifteen retained carbons of her telegrams to Stultz along with more that 70 additional telegrams of congratulations received from acquaintances and local businesses. Two telegrams sent by Richard Byrd to Stultz are also present.

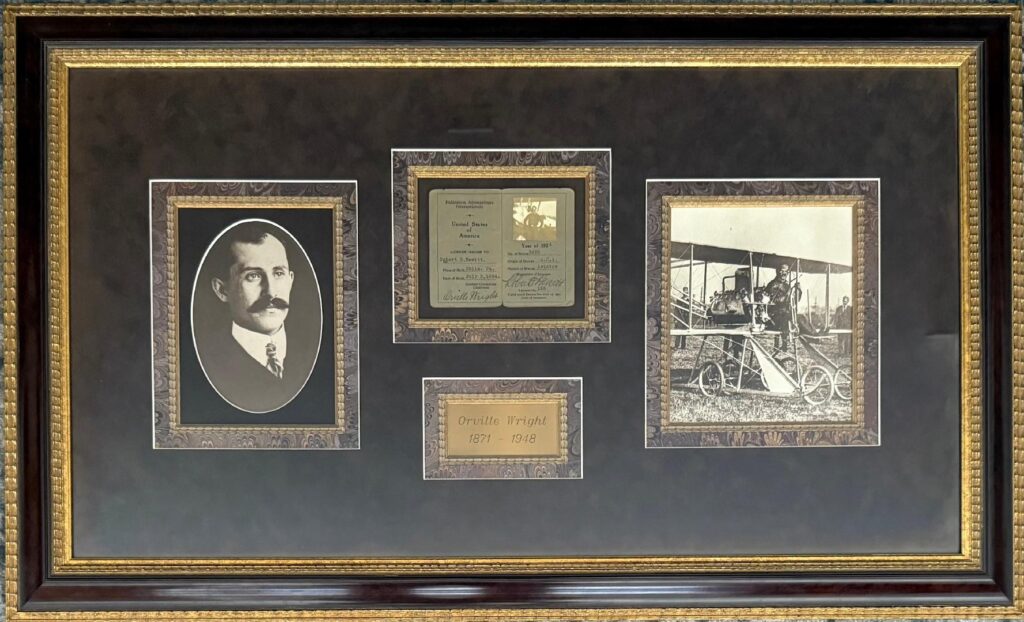

Together with Stultz’s pilot license for the year 1924, signed by none other than Orville Wright. The historic pilot’s license measures 5 x 4 inches (open) and includes a small snapshot of Stultz.

Lastly in the archive, is a souvenir booklet for the homecoming celebration held for Stultz in Williamsburg, Pennsylvania on July 18, 1928; and a trading card featuring Orville Wright.

THIS ARCHIVE IS ALL THE MORE FASCINATING AS IT DEPICTS THE ONGOING RACE BETWEEN MABEL BOLL AND AMELIA EARHART TO BECOME THE FIRST WOMAN TO CROSS THE ATLANTIC BY PLANE.

Mabel Boll (December 1, 1893 – April 11, 1949), known as the “Queen of Diamonds”, was an American socialite involved in the early days of record-setting airplane flights in the 1920s. She garnered nicknames from the press, including “Broadway’s most beautiful blonde” and the “$250,000-a-day bride”. She was intent on making history as the first woman to cross the Atlantic by plane.

Admiral Byrd and Charles A. Levine competed for the Orteig prize, but missed out. Each completed record flights shortly thereafter. While in Europe, Boll attempted to get Levine to fly her to America in the Columbia, which was still in France after a record-setting flight from New York. The inexperienced owner of the aircraft, Levine, had plans to fly it back to America with a French pilot, Maurice Droughin. After disagreements with Droughin and lawyers left the aircraft guarded and grounded, Levine took off to England claiming he was just testing the engine. (Chamberlain claimed that Levine bribed the guards.) Boll followed Levine to England by boat, talking Levine into letting her be a passenger.

Just before the flight, Levine’s new pilot, Capt. Walter G. R. Hinchliffe, publicly refused to fly if Boll was a passenger and instead, she flew to Rome, dropping a present to Benito Mussolini’s son. Boll was invited to try an east-west flight from America and she set out for New York by boat in January 1928.

On March 5, 1928, Wilmer Stultz, Oliver Colin LeBoutillier, and Boll on an improvised seat, made the first non-stop flight in the Columbia between New York City and Havana, Cuba, placing Boll on the front page of the New York Times. Boll was known as a temperamental passenger, once injuring pilot Erroll Boyd with an Alligator handbag in flight for making a premature landing in bad weather.

In 1928, the same teams that attempted to win the Orteig Prize were competing to be the first to fly a woman across the Atlantic (as a passenger). Levine chose the flamboyant Boll. On the other extreme, Amelia Earhart was chosen as a demure and capable pilot sponsored by George Palmer Putnam and Amy Phipps Guest.

On June 26, 1928, Boll was filmed leaving Roosevelt Field in the Columbia. Boll was later spotted 1,100 miles away in Harbour Grace, Newfoundland as a passenger in the Columbia. The aircraft was piloted by Oliver Colin LeBoutillier and Arthur Argles and owned by Columbia Aircraft Corp Chairman, Charles Levine. While Boll publicly announced her aspiration to be the first woman to fly across the Atlantic, Amelia Earhart was also in Newfoundland at the same time.

The newspapers focused their attention on the aspirations of Boll, known also as “The Diamond Queen of Broadway”. Preparations for the trip were done with full publicity. At the same time in relative secrecy, pilots Wilmer Stultz and Gordon were believed by the press to be preparing Byrd’s Fokker “Friendship” for his planned trip to the South Pole. Stultz himself planned to be the pilot of the Columbia and defected to Byrd’s crew. After several failed attempts days earlier, on June 17, the “Friendship” took off from the bay at Trepassey, Newfoundland with Earhart on board while the crew of the Columbia were grounded for five days due to the weather. Upon learning of successful flight by Earhart and crew, Boll returned to America.

Our archive includes a telegram from Mildred Stultz to Wilmer dated the day before, June 16th, stating, “Glad your getting good weather break in the morning. Putnam showed me plans you are going to win. Mabel can’t beat you. Godspeed and luck, Dear.”

Boll wanted a new nickname, “The Queen of the Air”. For her last serious record attempt, Levine purchased a customized long-range Junkers W 33 for $50,000 emblazoned with the logo “Queen of the Air” across the sides. Plans were made for Bert Acosta to fly Boll and Levine from Paris to New York for a new record, which was changed to a London to New York attempt. By the time the aircraft arrived in late August 1928, the flying season was coming to an end and Levine was preoccupied with legal matters in the United States. “The Queen of the Air” Junkers was transported back to America, damaged, and resold to William Rody. He renamed it to the “de Espírito Santo Agostinho” (ESA) and attempted a three-man transatlantic crossing record from Lisbon on September 13, 1931. The aircraft landed in the Atlantic Ocean, and the aircraft’s empty tanks kept the crew afloat for several days before they were rescued.

Mabel Boll died in relative obscurity in 1949 while Amelia Earhart became one of the most famous aviation pioneers in history.